My recent drive to Ban Don Yang refugee camp was…intense.

It took a little less than an hour to get to the camp from the larger town where my CWS colleagues and I had spent the previous night; but ultimately we didn’t travel all that far.

The problem was the road.

We were told that it’s impossibly muddy in the rainy season. Now, in the dry season, the caked mud made for very uneven ground. We were in a tough pickup truck; I can’t imagine how the families we saw on motorbikes fared.

In a lot of ways, that road is symbolic for a lot of what I saw that day in Ban Don Yang. The 2,000 refugees who live in this camp on the Thailand side of the border with Myanmar are, in theory, close to their Thai neighbors. But there are huge divides between them.

As violence ravaged their communities in Myanmar over the past several decades, tens of thousands of people fled across the border to Thailand. There are now nine camps on the Thailand side of the border; Ban Don Yang is the smallest.

While visiting with families, we heard stories of people who ran from their homes so quickly that they only brought the clothes on their back and some rice hastily stuffed into their pockets. Others told us about how they had moved around inside Myanmar for months, trying to evade soldiers, until they finally crossed into Thailand.

One woman told us that when she was in her 20s, she was visiting a friend away from home when her village fell to violence. She couldn’t go home and hasn’t seen her family since. She lives alone in Ban Don Yang. She managed to get word to her family at one point that she was alive and living in the camp. But that’s it.

The houses in Ban Don Yang are made from bamboo. Refugees are required to only build temporary structures because their situation is legally temporary; they cannot build sturdy, permanent homes.

It’s quiet in Ban Don Yang. By many standards, life here is comfortable. Food is provided through a debit card system, so people can go to shops in the camp to buy what they need. Local charcoal is provided as cooking fuel. There’s a school for children from kindergarten through grade 12. If a student wants to continue studying, there’s an informal university in one of the larger camps. There’s a clinic to visit if you get sick. All this support is available to people as they wait.

The problem is the waiting. There’s very little to do here except wait.

Refugees cannot legally leave the camp or work outside of it. If they want to go to university, it has to be the one in the other camp. Thailand may be all around them, but it may as well be thousands of miles away.

These parents in Myanmar’s Ayeyarwady Region told me about how they are using what they learned from CWS information sessions to make sure their daughter has a healthy diet.

A couple of years ago, I visited some CWS programs within Myanmar. The communities where we work are rural and remote; some are only accessible by boat for much of the year. Families in these communities face a whole list of challenges, from schools being far away to children being malnourished to annual flooding that submerges their source of clean water.

By many standards, life in Ban Don Yang is more comfortable than the life that families in these villages in Myanmar have.

But there’s one major difference that was palpable in Ban Don Yang: there is very little hope there. No drive. No motivation. No real thought for the future.

In Myanmar, I talked to people who were planning. They were putting systems into place to better prepare fore disasters. They were building platforms to elevate wells with hand pumps above the annual flood level. They were planting gardens to make sure their children had the right nutrition.

In Ban Don Yang, people were…waiting.

When we asked about their future, the only answer we got was about whether or not they would one day go home to Myanmar. There are formal ceasefires in place now, so in theory it’s safe to return. But, the ceasefires are not holding; and, after so many violent years, people aren’t sure what the future holds. Some people are considering returning, but for others it’s too dangerous and the risk of more trauma is too high. So, they wait.

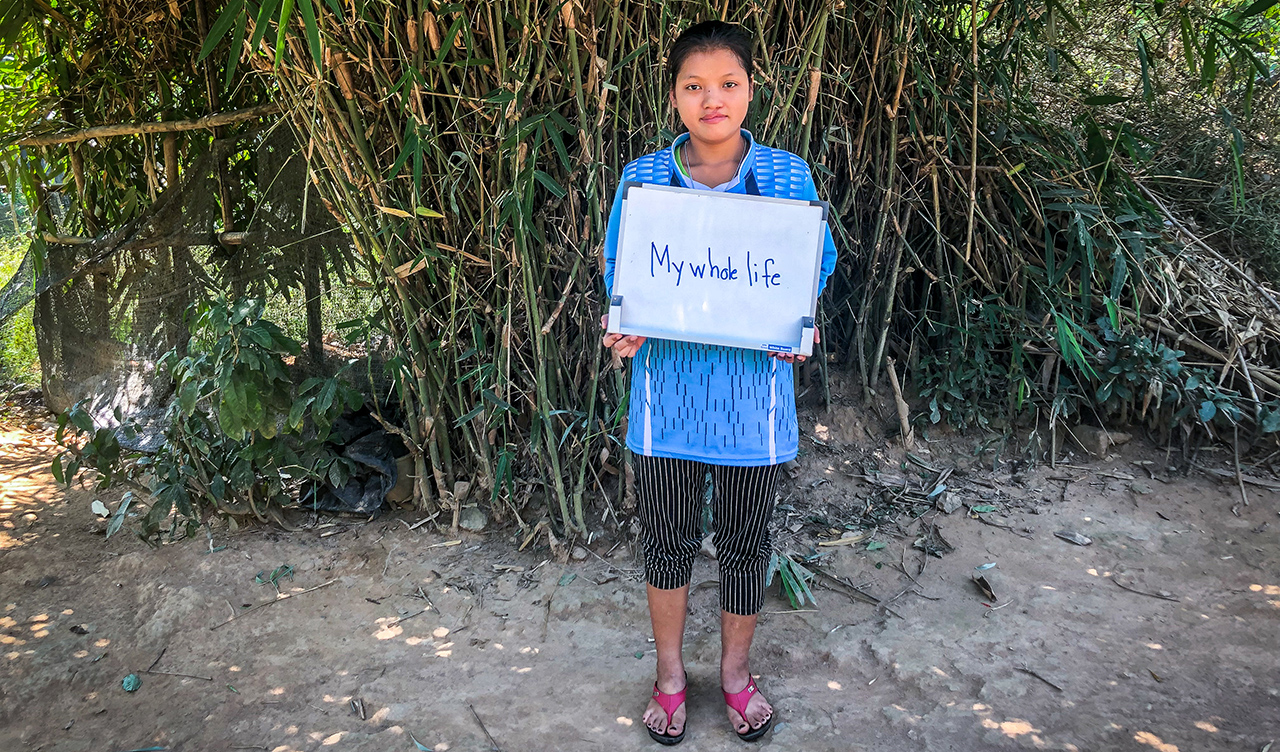

We asked some of the people we met to hold up a whiteboard that said how long they had lived in the camp. This young woman is 19.

The waiting goes on for a long time, too. We asked lots of people how long they had lived in the camp. For many, it was upwards of 18 years. One young woman told us it had been her whole life. She is 19.

As we bounced along our trip back to town later in the day – and many times since then – I’ve found myself thinking about those two different trips. I’ve thought about how proud I am to work for an organization that is supporting both groups of people in such different ways.

But mostly, I’ve thought about how much refugees lose when they are forced to flee to save their lives.

They lose houses, land and possessions. They lose any sense of a permanent home, and often all that is familiar to them. But in many cases, they lose even more than that. Even in the safety of another country, and even decades later, refugees who are caught in this endless cycle of waiting lose their motivation. They can lose their future, too.

And, as one of my colleagues framed it, when did hope become a luxury?

Laura Curkendall is the Director of Communications, Development and Humanitarian Assistance at CWS.

CWS supports The Border Consortium, which “is the main provider of food, cooking fuel, shelter and many other forms of support to more than 86,000 refugees from Burma/Myanmar in nine camps in Thailand.”