Note: This article was originally published in a newsletter by ACT Alliance. It is republished with their permission.

Note: This article was originally published in a newsletter by ACT Alliance. It is republished with their permission.

———————————————-

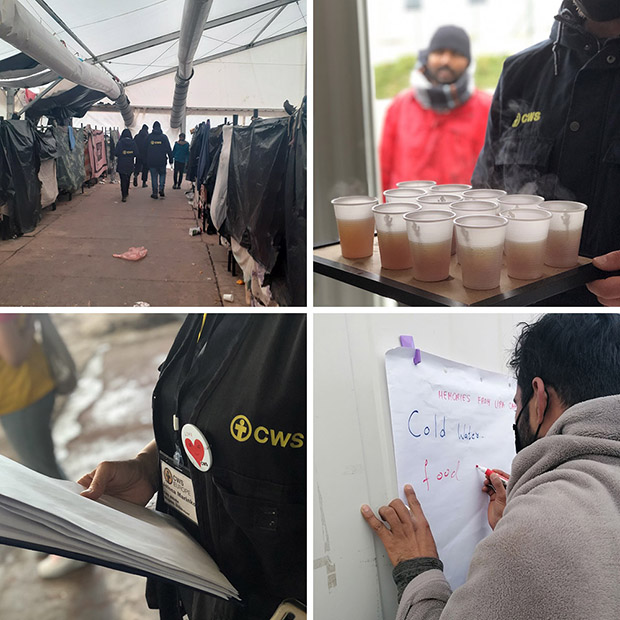

Bosnia saw a spike in new migrant and refugee arrivals in 2018. However, in 2020 the situation has escalated. Many migrants, including children, have been forced to live in outside makeshift settlements facing the harsh winter. Jovana Savic, CWS’s Regional Coordinator for Europe answers some questions to shed some light on what is happening in Lipa and other settlement centers.

Question: In the past few weeks, images of the situation migrants and asylum seekers are facing in Bosnia have shown the atrocious conditions in which women, men and children are living through this harsh winter. Can you tell us more about it?

Answer: The Lipa reception centre, 15 miles from the city of Bihac in Bosnia, was opened in April 2020 as an open-air, temporary tent centre with an agreement from the Bosnian government that they would upgrade the facilities to prepare for the cold weather by providing water, heating facilities and road access.

It was clear since beginning that Lipa was not suitable for winter, but all efforts to prepare the center or find other alternative solutions for the more than 1,400 people housed there failed. Since early December, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) stopped funding the Lipa centre and threatened to pull out as a way to react to the failure of authorities to meet their obligations.

On December 23, IOM finally pulled out of Lipa and other agencies like CWS were forced to follow suit. Before leaving, we delivered emergency kits, but that was definitely not enough. To add to the already inhumane living conditions migrants and asylum seekers were already experiencing in Lipa, a fire broke out and burned most of the tents and other facilities to the ground. The fire left those who sought shelter to fend for themselves. Groups of migrants tried to get to Bihac on foot but were intercepted by the police. To survive some had to quickly create or join already existing makeshift settlements around the Una-Sana canton, while an estimated 900 people returned to the burned out centre in Lipa, following the failed attempts to move them elsewhere.

Right now, Lipa’s residents are not allowed to leave. While recently the local authorities have installed 30 heated tents in Lipa, each with the capacity for about 30 people, the site still lacks access to running water and adequate sanitation. This poses a high risk to the health and safety of people there.

Right now, Lipa’s residents are not allowed to leave. While recently the local authorities have installed 30 heated tents in Lipa, each with the capacity for about 30 people, the site still lacks access to running water and adequate sanitation. This poses a high risk to the health and safety of people there.

The official closure of Lipa has increased the number of people sleeping outside. Around 3,000 people are currently sheltering in parks and forests, abandoned houses and factories or in outdoor makeshift settlements made of wood and tarps and are exposed to serious protection and health risks worsened by the pandemic. CWS is negotiating to join the outreach efforts and we expect to start in the next few weeks.

Q: The situation seems untenable. Is the Lipa center the only troubled settlement or you have seen similar patterns with other centers?

A: Unfortunately, Lipa is not the only settlement that has failed to provide support to people seeking refuge. A little over a year ago, we witnessed the closure of the improvised site in Vucjak, and four months ago Bira, one of the the largest reception facilities, was closed overnight. An estimated 700 single men from Bira were relocated to Lipa, which was already at full capacity. Meanwhile, 87 unaccompanied and separated children were transferred to another center called Borici. Of course, this relocation also left many people outside the centers. Right now, people are forced to sleep and endure unsafe and undignified living conditions while Bira remains fully equipped and empty.

The chaotic context makes civil society’s attempts to deliver aid difficult. CWS is trying to be flexible and quickly reorganizing and adapting, but it’s difficult.

This is a serious humanitarian and human rights crisis. People are living in inhumane conditions, and we cannot be indifferent to their suffering. As people of faith, we have a moral obligation to come together and call for the respect of human rights and the dignity of these women, men and children who are left to fend for themselves. This is unacceptable and mortifying.

Q: What are the next steps for CWS in Bosnia?

Q: What are the next steps for CWS in Bosnia?

A: With recent closures of the centers, CWS plans to expand the work done since 2018 to include mobile outreach teams to offer timely and immediate assistance to an increasing number of people who suddenly find themselves outside the official shelters. Our mobile outreach team will be able to identify vulnerable people sleeping in makeshift settlements -survivors of violence, unaccompanied children, families and people with serious medical needs -, refer them to specialized assistance and provide life-saving non-food items. We are appreciative of support from United Methodist Committee on Relief (UMCOR) to purchase supplies, which we will be distributing in the coming days.

The uncertainty and the hardships that migrants need to endure in Bosnia will not discourage arrivals. People will continue to arrive on their way to the EU, especially during the warmer months.

Outreach services, like our mobile teams, will be the only way to reach out to and offer first aid, basic support and comfort to people.

Especially concerning to us is the situation of unaccompanied minors residing outside the centers who remain completely invisible and are exposed to increased security, health and protection risks.

There are currently 200 unaccompanied children living in makeshift settlements. With the mobile outreach teams we aim at closing the circle of support and monitor the minors not just inside the official reception centers but also when they leave, are pushed back at the border, or decline a transfer to alternative accommodation in other cantons.

Longer-term, our ultimate hope is that enough humane, dignified reception facilities will be built and will be available to accommodate people on the move through the Una-Sana canton. We will continue to advocate for increased capacities and forge new partnerships along the way.

Unfortunately, we are seeing increasing episodes of criminalization of people on the move, who are accused to be security and health threats just to draw political capital. This hate language is dangerous. As first responders, we are worried and we see the need to change this narrative and counter this perception with more positive and fact-based storytelling which in the end will contribute to a richer and more complex migration discourse.