Representatives of both groups during negotiations which lead to a landmark agreement on traditonal uses of Indigneous People´s land and re-settlelement of criollo cattle farmers. Photo: Paul Jeffrey / CWS

In the heart of the Argentinean Chaco a dusty seven hours by road from the nearest city of Salta is Lote Fiscal 14-55. One of the areas with the highest levels of poverty in the country, it is also one of the largest land claims in all of South America involving 1576, 532 acres of land, 70 indigenous communities and 468 non-indigenous cattle farming families known as criollos. Their story is landmark example of dialogue, consensus-building and mutual understanding between two groups both of whom live in extreme poverty but who have very different visions of what land means: while the indigenous see the land as communal, the criollos see it as a private property, cattle ranching – the livelihood of the criollos requires fences but this prevents the indigenous from hunting and gathering freely while overgrazing and deforestation lead to a decline in the availability of honey and fruits – a staple of the indigenous diet.

The solution? A dialogue process between the two groups at the heart of which was a participatory mapping process to find ways of living in harmony.

The indigenous and criollo agreed that it did not make sense to be segregated given that after over 200 years of being neighbours they are dependent on each other in critical ways, despite their differences.

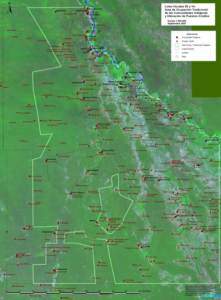

In a process supported by a number of organizations including Chaco Program member Fundapaz, GPS and GIS were used to develop a map of all the criollo farms and indigenous communities, areas that were overpopulated or overgrazed, where use of land between the two groups overlapped and areas that had not yet been exploited. On the basis of this, and after 15 years of fragile and frought negotiations, an agreement was finally reached: The indigenous would get legal title to 988,000 acres, the criollos 600,000, and a number of criollos would move to less inhabited areas on the grounds that extensive support for water infrastructure and silvopastoral land management plans would be received.

The basis for negotiations in 55-14 was this map showing the overlap between areas used by criollos and Indigenous Peoples. Map courtesy of FUNDAPAZ.

On 10 June 2014 the Government signed a decree handing over legal title to the two groups using their map as the basis for the land tenure agreement. Since then CWS Chaco Program has been working with them on the development of productive activities to improve their food security and build sustainable communities.

In July 2015 three criollo families re-located, as the agreement stipulated, and Chaco Program worked with them to develop a map and an inventory of the flora and fauna so that they can plan how best to use their newly acquired 1100 acres of land in a productive and sustainable way.

“The indigenous people don’t like our animals,” said Esmerito Arenas of the Organization of Criollo Families (OFC) “but to us, cattle are survival. It is our livelihood. Today 468 criollo families and 70 indigenous communities can plan for the future. Some criollo families volunteered to re-locate during the dialogue process. It is not easy for them – for generations these families have lived in the same place and some are moving to an area 80-90km away. What helps them feel more secure about moving is having a map of their new land and a plan for how to manage it.”

At the same time Chaco Program in partnership with two sister organizations Asociana and Fundacion Siwok is working with indigenous communities to develop a production plan based on kitchen gardens using drip irrigation. The first step was the development of a map of already existing gardens and new areas opened up to indigenous communities due to the agreement reached with the criollos not to graze cattle.

“The expansion of criollo farms and overgrazing of cattle caused the destruction of the forest,” says indigenous leader Francisco Perez, “Now it is totally forbidden for criollosto graze animals or put up fences inside the 988,000 acres. And so slowly, we will be able to repair the damage that was done and we hope the honey and fruits of the forest will return with abundance.”

Community Mapping is a key component of CWS Chaco Program which works to strengthen the capacity of indigenous men and women to recover parts of their ancestral territories and develop productive activities to improve their food security. Without concrete maps delineating their land claims or recovered land, communities are vulnerable to losing it to governments and investors for economic and commercial development. Using a participatory process that involves the whole community in the development of the map, a team of indigenous experts in GPS and GIS has also been trained who provide continued support to communities. The program is supported by Presbyterian Hunger Program. www.presbyterianmission.org/ministries/hunger/grants

Fionuala Cregan is CWS’s Program Officer for the South American Chaco.